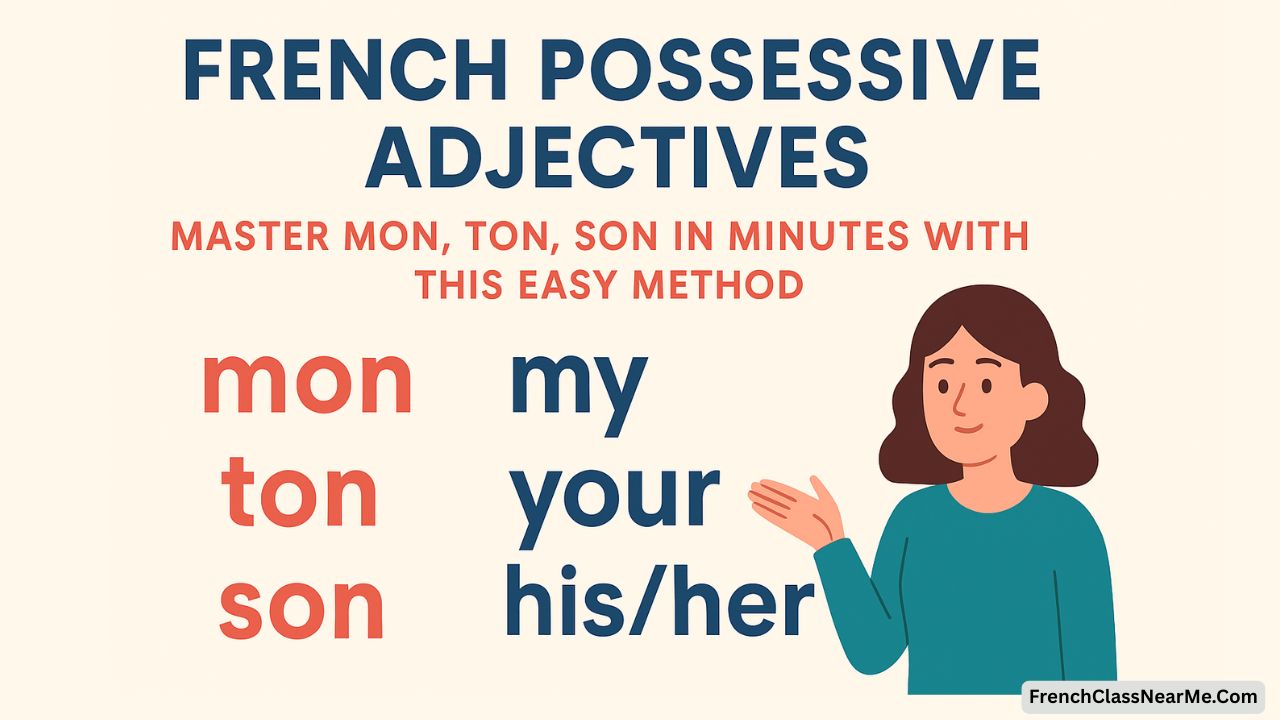

French Possessive Adjectives: Master Mon, Ton, Son In Minutes With This Easy Method

Last Updated: November 16, 2025

Author: Issiak Balogun Ayinla — French language educator and content creator helping English speakers learn French with clarity and confidence. I simplify grammar, pronunciation, and everyday conversation so you can speak naturally in real-life situations.

The ability to understand french possessive adjectives: master mon, ton, son in minutes with this easy method starts with recognizing how often these little words show up in everyday French sentences. Even simple expressions like “my friend,” “your house,” or “his sister” instantly require the correct form. These words seem tiny, but they carry essential meaning, and using the wrong one can completely change what someone thinks you’re saying.

French Possessive Pronouns: The Complete Breakdown Your Teacher Never Gave You

French learners often struggle with possessive adjectives because the rules feel different from English. In English, everything depends on who owns the object. In French, however, the form depends on the gender and number of the noun being owned, not the owner. That single difference creates most of the confusion. But once the method becomes clear, choosing between mon, ton, son, and all the other forms feels natural.

Now that the importance of possessive adjectives is clear, this article breaks everything down using simple explanations, natural examples, and mobile-friendly tables that help learners master the patterns quickly. The goal is not just to explain the rules, but to make them feel intuitive, clear, and easy to apply in real conversations.

Why Understanding French Possessive Adjectives Feels Hard At First

Many learners think they understand the rule, but make mistakes when speaking because their brain wants to match the possessive to the owner, just like in English. For example, it seems logical to say sa frère because you’re talking about “her brother,” but French focuses on the noun frère (masculine), not the person who owns it.

Another challenge comes from seeing forms that look almost identical. Words like mon / ma / mes or son / sa / ses can appear overwhelming at first glance. That feeling is normal. French packs a lot of meaning into short words, but once the structure becomes clear, patterns start to appear everywhere.

Common textbooks often explain the rules too vaguely or skip practical examples altogether, leaving learners confused. That’s why this guide relies on simple sentences, clear reasoning, and real-life usage, making the concepts stick.

What Possessive Adjectives Are (In The Most Simple Explanation)

Possessive adjectives are small words that show ownership. In English, they are words like my, your, his, her, our, their. In French, the equivalent words must match the noun they describe. That is the key difference.

Here is the most important principle:

In French, the possessive adjective must agree with the thing being owned — not the person who owns it.

This single rule unlocks 90% of the confusion.

To understand this, look at this simple comparison:

| English | French |

|---|---|

| My car | Ma voiture (car = feminine) |

| My book | Mon livre (book = masculine) |

| His sister | Sa sœur (sister = feminine) |

| Her brother | Son frère (brother = masculine) |

Even when talking about “her brother,” French uses son because frère is masculine. The owner doesn’t matter. The noun does.

With that said, it’s time to look at the three forms beginners encounter first: mon, ton, and son.

Mon, Ton, Son: The Core Idea Behind The First Three Possessives

Mon, ton, and son are the masculine singular forms of the three most frequently used possessive adjectives in French. They pair with masculine nouns or feminine nouns starting with a vowel sound (a special rule discussed later).

Here is the basic idea:

- mon = my (masculine singular noun)

- ton = your (masculine singular noun, informal)

- son = his or her (masculine singular noun)

One misunderstanding beginners often have is believing that son means “his” and sa means “her.” But son/sa do not express the gender of the owner. They express the gender of the noun.

This matters because son can mean “his” or “her” depending on the situation:

- son frère = his brother OR her brother

- son livre = his book OR her book

Only context tells the listener who owns the object.

Examples Of Mon, Ton, Son In Action

Below are some natural sentences that show how French chooses the form based on the noun:

- mon pantalon = my pants (masculine noun)

- ton chien = your dog (masculine noun)

- son sac = his/her bag (masculine noun)

And with feminine nouns starting with vowels:

- mon amie = my (female) friend

- ton idée = your idea

- son école = his/her school

The vowel rule appears frequently in daily speech, which surprises many learners. But the idea is simple: French avoids vowel clashes to make pronunciation smoother.

Now that these concepts are becoming clearer, the next step is seeing how gender affects the choice.

How Gender Of The Noun Controls The Possessive Form

French nouns have grammatical genders. Some are masculine, some feminine, and possessive adjectives must match that gender. This means learners must think not only about ownership, but also about the noun itself.

Here is a simple table to show how the owner does not affect the choice:

| Noun | Gender | My | Your (Informal) | His/Her |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Livre (book) | Masculine | mon livre | ton livre | son livre |

| Voiture (car) | Feminine | ma voiture | ta voiture | sa voiture |

| Ami (friend, m.) | Masculine | mon ami | ton ami | son ami |

| Amie (friend, f.) | Feminine (but starts with vowel) | mon amie | ton amie | son amie |

In short, French possessive adjectives always follow the noun’s gender, not the speaker’s identity.

When Meaning Changes Because The Noun Changes

The same person can use two different forms depending on the object they are describing:

- ma lampe = my lamp (feminine noun)

- mon ordinateur = my computer (masculine noun)

- mes livres = my books (plural noun)

Changing the noun changes the possessive form. English does not have this complexity, which is why learners need practice before the forms become automatic.

To make this easier, here is a simple sentence transformation example:

English: Her phone

French: Son téléphone (masculine noun)

English: Her car

French: Sa voiture (feminine noun)

Seeing the difference visually makes the rule more intuitive.

A Beginner-Friendly Comparison Table For Mon, Ton, Son

| French Possessive | When To Use It | Example |

|---|---|---|

| mon | masculine noun OR feminine noun starting with a vowel | mon frère, mon ami |

| ton | masculine noun OR feminine noun starting with a vowel (informal you) | ton chien, ton idée |

| son | masculine noun OR feminine noun starting with a vowel (his/her) | son père, son école |

This table clarifies the essential idea:

mon, ton, and son appear only when the noun is masculine OR begins with a vowel sound.

Now that the foundation is firmly in place, the next part of the article expands the system to include the full set of French possessive adjectives — including feminine forms, plural forms, and the ones used for “our,” “your,” and “their.”

Full Breakdown Of All French Possessive Adjectives

Now that the foundation for mon, ton, and son is clear, the next step is to learn the entire system of French possessive adjectives. This is where most learners finally understand how everything fits together. The key idea remains the same: the form you choose must always agree with the noun in gender and number.

The full list of French possessive adjectives falls into three groups:

- Possessives for I, you, he/she

- Possessives for we, you (plural/formal)

- Possessives for they

Each group includes masculine, feminine, and plural forms. The patterns are predictable once you see them laid out clearly.

Mon, Ma, Mes: Talking About “My”

These three forms all mean my, but they change based on the noun:

| Form | Used With | Example |

|---|---|---|

| mon | masculine noun OR feminine noun starting with a vowel | mon frère, mon amie |

| ma | feminine noun (not starting with a vowel) | ma maison |

| mes | plural nouns | mes amis, mes voitures |

One thing to notice is that mon is used before a feminine noun beginning with a vowel sound. French prefers smoother pronunciation and avoids repeating vowel sounds back-to-back.

Examples In Real Sentences

- mon cahier = my notebook

- ma tablette = my tablet

- mes enfants = my children

- mon école = my school (école starts with a vowel)

- mes idées = my ideas

In short, choose between mon/ma/mes by looking only at the noun that follows.

Ton, Ta, Tes: Talking About “Your” (Informal Singular)

These forms apply when speaking to someone casually (friends, family, same age group).

| Form | Used With | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ton | masculine noun OR feminine noun starting with a vowel | ton cousin, ton amie |

| ta | feminine noun | ta chaise |

| tes | plural nouns | tes chaussures |

Many beginners forget that ta changes to ton before a vowel for the sake of smooth pronunciation.

Examples In Real Sentences

- ton stylo = your pen

- ta voiture = your car

- tes parents = your parents

- ton histoire = your story (histoire begins with a vowel sound)

Because ton/ta/tes follow the same pattern as mon/ma/mes, learning them becomes much easier.

Son, Sa, Ses: Talking About “His” And “Her”

This is the set that confuses English speakers the most. Remember that these forms reflect the gender of the noun, not the owner.

| Form | Used With | Means | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| son | masculine noun OR feminine noun starting with a vowel | his/her | son chat |

| sa | feminine noun | his/her | sa maison |

| ses | plural nouns | his/her | ses livres |

Examples In Real Sentences

- son frère = his brother OR her brother

- sa sœur = his sister OR her sister

- ses idées = his ideas OR her ideas

- son amie = his (female) friend OR her (female) friend

Context, not the word itself, tells you whether you mean “his” or “her.”

With these three sets complete, the next group expresses “our,” “your,” and “their.”

Notre, Nos: Talking About “Our”

This group is simpler because French does not change the form based on gender. There is only a singular and a plural form.

| Form | Used With | Example |

|---|---|---|

| notre | singular nouns (any gender) | notre maison, notre frère |

| nos | plural nouns | nos enfants, nos amis |

Notre and nos work the same for masculine and feminine nouns, which makes them more predictable.

Examples In Real Sentences

- notre appartement = our apartment

- notre fille = our daughter

- nos voisins = our neighbors

- nos projets = our plans

This group helps learners relax a little — the rules feel straightforward here.

Votre, Vos: Talking About “Your” (Plural Or Formal)

Votre and vos follow the same structure as notre/nos. They do not depend on noun gender, only on number.

| Form | Used With | Example |

|---|---|---|

| votre | singular nouns (any gender) | votre idée, votre père |

| vos | plural nouns | vos amis, vos documents |

Examples In Real Sentences

- votre rendez-vous = your appointment

- votre famille = your family

- vos chaussures = your shoes

- vos projets = your projects

The key difference is simply that votre/vos applies to formal you or you plural.

Leur, Leurs: Talking About “Their”

Like notre and votre, this group does not depend on gender.

| Form | Used With | Example |

|---|---|---|

| leur | singular nouns | leur maison |

| leurs | plural nouns | leurs enfants |

Examples In Real Sentences

- leur idée = their idea

- leur professeur = their teacher

- leurs chats = their cats

- leurs voitures = their cars

Learners often overthink this one, but the pattern is consistent: singular noun → leur, plural noun → leurs.

All Possessive Adjectives In One Table

| Owner | Masculine Sing. | Feminine Sing. | Before Vowel (F) | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My | mon | ma | mon | mes |

| Your (informal) | ton | ta | ton | tes |

| His/Her | son | sa | son | ses |

| Our | notre | notre | n/a | nos |

| Your (formal/plural) | votre | votre | n/a | vos |

| Their | leur | leur | n/a | leurs |

This table gives a complete overview without overwhelming the learner. The next step is to reinforce everything with real-life sentences that show the patterns in action.

Examples Of Every Possessive In French Sentences

Here are sample sentences that illustrate each form in meaningful, everyday contexts:

Talking About “My”

- mon lit est confortable

- ma veste est nouvelle

- mes amis arrivent bientôt

Talking About “Your” (Informal)

- ton film préféré est lequel ?

- ta chambre est très jolie

- tes messages sont importants

Talking About “His/Her”

- son chien est très calme

- sa mère travaille à Paris

- ses projets sont ambitieux

Talking About “Our”

- notre professeur est patient

- notre ville est magnifique

- nos enfants adorent voyager

Talking About “Your” (Formal/Plural)

- votre commande est prête

- votre clé est à l’accueil

- vos documents sont complets

Talking About “Their”

- leur décision semble logique

- leur appartement est moderne

- leurs amis habitent à Lyon

These examples help learners visualize how French possessives appear in everyday life.

Now that all forms are clear, we will explore advanced rules, exceptions, vowel interactions, common mistakes, and natural dialogues.

Advanced Rules That Make French Possessive Adjectives Much Easier

Now that the full chart of mon/ma/mes through leur/leurs is clear, it’s time to dig into the rules that most learners never discover until much later. These details explain why some phrases look “wrong” at first glance and why native speakers choose certain forms instinctively. Understanding these advanced rules unlocks the final layer of confidence.

The “Ma” Changes To “Mon” Before A Vowel Rule

This is one of the most unique features of French possessive adjectives, and it often surprises learners.

French avoids having two vowel sounds crash into each other. To keep pronunciation smooth, “ma” becomes “mon” before a feminine noun beginning with a vowel or silent ‘h’.

This is not about gender. It’s about sound.

Examples

- mon amie (not ma amie)

- mon histoire (not ma histoire)

- mon école (not ma école)

- mon assiette (not ma assiette)

The noun is still feminine — only the possessive changes.

This rule exists purely for pronunciation. French likes smooth vowel transitions, so it borrows the masculine form to protect the flow of speech.

The Same Rule Applies To “Ta” And “Sa”

Just like with “ma,” the forms ta and sa change to ton and son before feminine nouns starting with a vowel sound.

Examples

- ton idée (not ta idée)

- ton entreprise (not ta entreprise)

- son activité (not sa activité)

- son habitude (not sa habitude)

In short, mon, ton, son appear whenever the next word begins with a vowel sound, even if that noun is feminine.

This is one of the most common areas where beginners make mistakes, and mastering this rule instantly makes speech sound more natural.

Why “Son” Can Mean Both “His” And “Her”

Many learners feel confused the first time they see that son can mean “his” or “her.” But the logic is simple:

French does not care about the owner’s gender. It only cares about the noun’s gender.

English:

- his brother

- her brother

French:

- son frère (same for both)

English:

- his idea

- her idea

French:

- son idée (same for both, because idée starts with a vowel)

Only context reveals the owner:

- Marie adore son frère. → “Her brother”

- Paul adore son frère. → “His brother”

This is completely normal in French and never confuses native speakers because the context always makes the meaning clear.

Special Cases With Body Parts

Body parts use possessive adjectives in a way that confuses English speakers because French sometimes avoids using possessives entirely.

In French, body parts often appear with the definite article le/la/les instead of possessives when the owner is already clear.

Compare the two languages:

English: I washed my hands.

French: Je me suis lavé les mains.

English: She brushed her teeth.

French: Elle s’est brossé les dents.

English: He hurt his leg.

French: Il s’est fait mal à la jambe.

Possessive adjectives still appear when specifically needed:

- ma main = my hand

- son coude = his/her elbow

- ta tête = your head

But in reflexive actions, French often uses articles, not possessives.

Understanding this prevents unnatural French like: je me suis lavé mes mains (incorrect).

Possessive Adjectives Versus Articles (Le/La/Les)

Another area where students get confused is knowing whether to use a possessive or a regular article.

Use a possessive when:

- ownership must be identified

- the noun could belong to anyone

- the speaker needs to be precise

Examples:

- ma voiture → my car

- ton passeport → your passport

- leur appartement → their apartment

Use an article when:

- the owner is obvious from the sentence

- the action is reflexive

- the noun is used in general statements

Examples:

- Ils ont fermé les yeux. (They closed their eyes.)

- Je me coupe les cheveux. (I’m cutting my hair.)

Recognizing these patterns helps learners avoid overusing possessives.

Possessive Adjectives Versus Demonstratives (Ce/Cet/Cette/Ces)

Learners often mix up possessives (mon, son, leur) with demonstratives (ce, cette), but they function differently.

Possessives show ownership.

Demonstratives point to something.

Examples:

- mon livre = my book

- ce livre = this book

- sa maison = his/her house

- cette maison = this house

Using the wrong one changes the meaning completely, so distinguishing them is essential.

Regional Usage Notes (France, Canada, Belgium, Switzerland)

Possessive adjectives remain consistent across French-speaking regions, but pronunciation may vary:

- In Quebec, “mon amie” often sounds like “mon am’ie” (slightly blended)

- In France, “son” and “sa” are often spoken with softer consonants

- In Switzerland, the plural forms “nos” and “vos” may sound more open

These differences do not affect grammar; they only affect accent.

Natural-Sounding French Dialogues Using Possessive Adjectives

Seeing possessives in real conversations helps learners make the rules automatic.

Dialogue 1: Talking About Family

Paul: Tu as vu ma sœur ?

Marie: Oui, son train est arrivé tôt.

Paul: Elle a pris ses valises ?

Marie: Oui, toutes ses affaires sont là.

Dialogue 2: Meeting Friends

Claire: Où est ton ami ?

Léo: Mon ami arrive avec sa voiture.

Claire: Ses parents viennent aussi ?

Léo: Non, ils préparent leur maison pour demain.

Dialogue 3: At School Or Work

Julia: Notre professeur a rendu vos devoirs.

Marc: Mes notes étaient bonnes ?

Julia: Oui, ton travail était excellent.

Dialogues make the rules feel alive and practical.

Practice Exercises To Reinforce The Rules

Here are some exercises learners can use to test comprehension.

Exercise 1: Choose The Correct Possessive

- ______ voiture est rouge. (my)

- Il adore ______ sœur. (his/her)

- Où sont ______ clés ? (your, informal)

- Nous avons vendu ______ livres. (our)

- Elle a perdu ______ téléphone. (her)

Answers

- ma voiture

- sa sœur

- tes clés

- nos livres

- son téléphone

Exercise 2: Rewrite Using The Correct Form

- ma amie → mon amie

- ta histoire → ton histoire

- sa école → son école

Exercise 3: Fill In The Blanks

- Ils aiment ______ appartement. (their)

- Je prends ______ sac. (my)

- Vous avez oublié ______ documents. (your, formal)

- Il a trouvé ______ montre. (his)

- Tu dois appeler ______ mère. (your, informal)

Answers

- leur appartement

- mon sac

- vos documents

- sa montre

- ta mère

These exercises help learners internalize the patterns so they can use them naturally in conversation.

A Final Review Before Moving To The FAQs

Possessive adjectives become easy once the learner understands:

- They match the noun, not the owner

- “Mon/ton/son” appear before vowel sounds

- Context determines “his” or “her”

- Articles often replace possessives with body parts

- Plural forms are consistent across all genders

Frequently Asked Questions About French Possessive Adjectives

What Is The Main Rule Behind French Possessive Adjectives?

The main rule is that French possessive adjectives must agree with the gender and number of the noun they refer to, not the gender of the owner. This is why son frère can mean “his brother” or “her brother.” Once learners focus on the noun instead of the owner, the system becomes much clearer and more predictable.

Why Does “Ma” Change To “Mon” Before A Vowel?

French avoids putting two vowel sounds next to each other because it disrupts the flow of speech. To keep pronunciation smooth, ma becomes mon before feminine nouns starting with a vowel or silent h. The gender of the noun never changes—only the form of the possessive shifts to make the sentence sound natural.

How Do I Know Whether “Son” Means His Or Her?

Context always determines whether son means “his” or “her.” French doesn’t encode the owner’s gender in the possessive adjective. Instead, the form matches the noun’s gender. If the sentence doesn’t make ownership obvious, speakers add clarifying phrases like son frère à Marie to remove ambiguity when necessary.

What Is The Difference Between “Ton” And “Votre”?

Ton is used for speaking informally to a single person, while votre applies to formal situations or when addressing more than one person. Both mean “your,” but their usage depends on politeness and number. In everyday conversation, French speakers choose between them based on social distance and the relationship with the listener.

When Should I Use “Mes,” “Tes,” Or “Ses”?

Use these forms whenever the noun is plural. Mes means “my,” tes means “your” (informal), and ses means “his” or “her.” The plural form does not change based on gender, which simplifies usage. Anytime the noun ends in s or exists in multiple units, the plural possessive is required.

Why Does French Use Articles Instead Of Possessives With Body Parts?

French often uses definite articles with body parts when the owner is already clear from the sentence, especially in reflexive actions. Sentences like je me suis lavé les mains follow a structure where the reflexive pronoun shows ownership. Possessives appear only when distinguishing one person’s body part from another’s.

Do Possessive Adjectives Change In Negative Sentences?

No, possessive adjectives remain the same in both affirmative and negative sentences. Only the surrounding structure changes. For example, c’est mon livre becomes ce n’est pas mon livre. The possessive keeps its original form because the relationship between owner and noun does not change with negation.

How Do Plural Possessives Work With Feminine And Masculine Nouns?

Plural forms ignore gender entirely. Mes, tes, ses, nos, vos, and leurs work for both masculine and feminine plural nouns. This consistency simplifies learning because once the noun is plural, the only decision left is choosing the correct owner, not the noun’s gender.

Why Do Some Nouns That Start With H Use “Mon”?

Some French h’s are silent, meaning the word begins with a vowel sound. In those cases, French swaps ma for mon to keep pronunciation smooth. Words like histoire or habitude fall into this category. However, nouns with an aspirated h, like héros, keep the feminine form because the h behaves like a consonant.

Can “Leur” Ever Take An S Before A Singular Noun?

No, leur never takes an s before a singular noun. The form leurs is strictly plural and only appears when the noun following it is plural. French never adds an s to match multiple owners. The presence or absence of the final s depends entirely on whether the owned object is singular or plural.

How Can I Quickly Choose Between Mon, Ma, And Mes?

Look at the noun first. If it’s masculine, choose mon. If it’s feminine, choose ma, unless it begins with a vowel sound—then switch to mon. For plural nouns, always use mes. With practice, your brain automatically connects noun types to the correct possessive form without hesitation.

What Is The Difference Between “Sa Voiture” And “La Voiture”?

Sa voiture means “his car” or “her car,” while la voiture means “the car.” The possessive indicates ownership, whereas the article simply identifies or refers to the noun. French speakers choose between them depending on whether they want to emphasize possession or simply describe the object itself.

Do Possessive Adjectives Change In Questions?

No, possessive adjectives stay exactly the same in questions. What changes is the order of the sentence or the intonation. For example, c’est ton sac becomes c’est ton sac ? or est-ce ton sac ? The grammar of the possessive remains unchanged in all types of questions.

How Do I Use Possessives With Friends And Family Vocabulary?

Possessives frequently appear with family and friend vocabulary. You choose the form based on the noun: mon frère, ma sœur, mes cousins. When dealing with feminine nouns starting with vowels, the form shifts to mon: mon amie or mon épouse. Mastering these forms allows learners to speak naturally about relationships.

Do Gender Rules Apply Even When Talking About Inanimate Objects?

Yes, the same rules apply regardless of whether the noun refers to a person, object, idea, or place. French assigns grammatical gender to all nouns, and possessive adjectives follow that gender. For example: ma table, mon téléphone, son projet. The concept of gender applies grammatically, not biologically.

Can You Use Possessives Without Mentioning The Noun?

Yes, French sometimes omits the noun when the meaning is clear from context, especially with family words. For example, c’est ton frère ou le mien ? means “Is that your brother or mine?” The possessive stands alone when the noun is already understood by both speakers.

Why Does French Not Use Apostrophes In Possessives Like English Does?

French expresses possession through possessive adjectives or structural phrases rather than apostrophes. English phrases like “Maria’s book” become le livre de Maria or son livre depending on context. French avoids apostrophes for ownership and uses grammatical agreements instead.

Are Possessive Adjectives The Same In Formal Writing And Casual Speech?

Yes, the forms themselves do not change between formal and casual contexts. The only adjustment is choosing between ton and votre depending on politeness. In spoken and written French, possessive adjectives follow the same agreement rules with no stylistic variations.

Do Children Learn Possessives Differently From Adults?

Children instinctively learn possessives by listening to patterns in speech, while adults rely more on conscious grammar rules. Despite this difference, the rules themselves stay the same. Regular exposure to examples and simple repetition help adults internalize possessive forms nearly as effectively as native-speaking children.

How Do Possessives Work With Professions?

When referring to professions, choose the possessive based on the noun. For example: son médecin, ma professeure, vos avocats. French aligns the possessive with the gender and number of the profession itself, making it a straightforward application of the standard agreement rules.

What Is The Quickest Way To Master Son/Sa/Ses?

The fastest method is to memorize that these forms match the noun, not the owner. Practice by pairing each form with typical masculine, feminine, or plural nouns. Reading short dialogues or sentences reinforces the patterns and helps the brain automatically select the correct form during real conversations.

How Do I Choose Between Votre And Vos When Speaking To One Person?

Use votre when the noun is singular and vos when the noun is plural, regardless of the number of people you’re speaking to. The form you choose always depends on the noun following it. Even in a one-to-one conversation, vos projets is correct if the projects are plural.

Do Possessive Adjectives Ever Change Meaning Based On Context?

Yes, especially with forms like son and sa, where the owner’s gender isn’t visible. Depending on the sentence, son chien could mean “his dog” or “her dog.” French relies heavily on context and background information to clarify ownership when the possessive itself doesn’t specify it.

Why Does French Use The Same Possessive For His And Her?

French ties possessive forms to the grammatical gender of the noun, not the biological gender of the owner. This system streamlines agreement because speakers only need to look at the word being possessed. It may feel unusual to English speakers, but it simplifies many constructions and reduces ambiguity in speech.

What Happens When The Owner Is A Group Of People?

When the owner is a group, French uses plural forms like leur or leurs. Unlike English, French never adds an s to match multiple owners before a singular noun. For example, leur maison always means “their house,” whether the owner is two people or twenty. The noun drives the agreement.

Can French Possessive Adjectives Stand Alone In Answers?

Yes, possessives often appear alone in responses when the noun is clear. If someone asks, C’est ton stylo ? you may reply, Non, c’est le sien. These standalone forms behave like pronouns and help avoid repeating the noun unnecessarily. The listener fills in the missing context from the previous sentence.

Are Plural Possessives Harder Than Singular Ones?

Plural possessives are generally easier because they ignore gender. Once you know who owns the plural noun, the form becomes obvious: mes, tes, ses, nos, vos, or leurs. These patterns remain consistent across all types of nouns, making them more predictable than singular forms that require gender awareness.

Which Mistakes Do English Speakers Make Most Often With Possessives?

English speakers often use the possessive based on the owner instead of the noun, leading to errors like sa frère. They may also forget the vowel rule, producing incorrect phrases like ma amie. Mixing up votre/vos and ton/ta is another frequent challenge. Practice with common vocabulary helps eliminate these mistakes.

How Important Are Possessive Adjectives For Fluency?

Possessive adjectives appear constantly in everyday French—talking about family, describing your home, expressing preferences, or explaining plans. They form part of the core grammar needed for natural conversation. Once learners master them, speaking becomes smoother, clearer, and more precise because they can express ownership without hesitation.

Conclusion

French possessive adjectives may seem confusing at first, but understanding how each form connects to the noun makes the entire system fall into place. Once learners memorize that the adjective agrees with what is owned, not who owns it, everything becomes more intuitive. Now that the full structure is clear, the rules, exceptions, vowel changes, and everyday usage feel much easier to apply in real conversations. This foundation helps learners speak naturally, describe relationships accurately, and build sentences with confidence across all daily situations.